Long before the vibrant petals of flowers appeared, ancient plants relied on heat to lure in pollinators. A new study published in Science reveals that cycads – a group of tropical plants resembling palms – generate significant warmth in their reproductive structures to attract beetles. This discovery provides insight into the earliest forms of pollination, predating the evolution of flowers by millions of years.

How Heat Works as a Pollination Signal

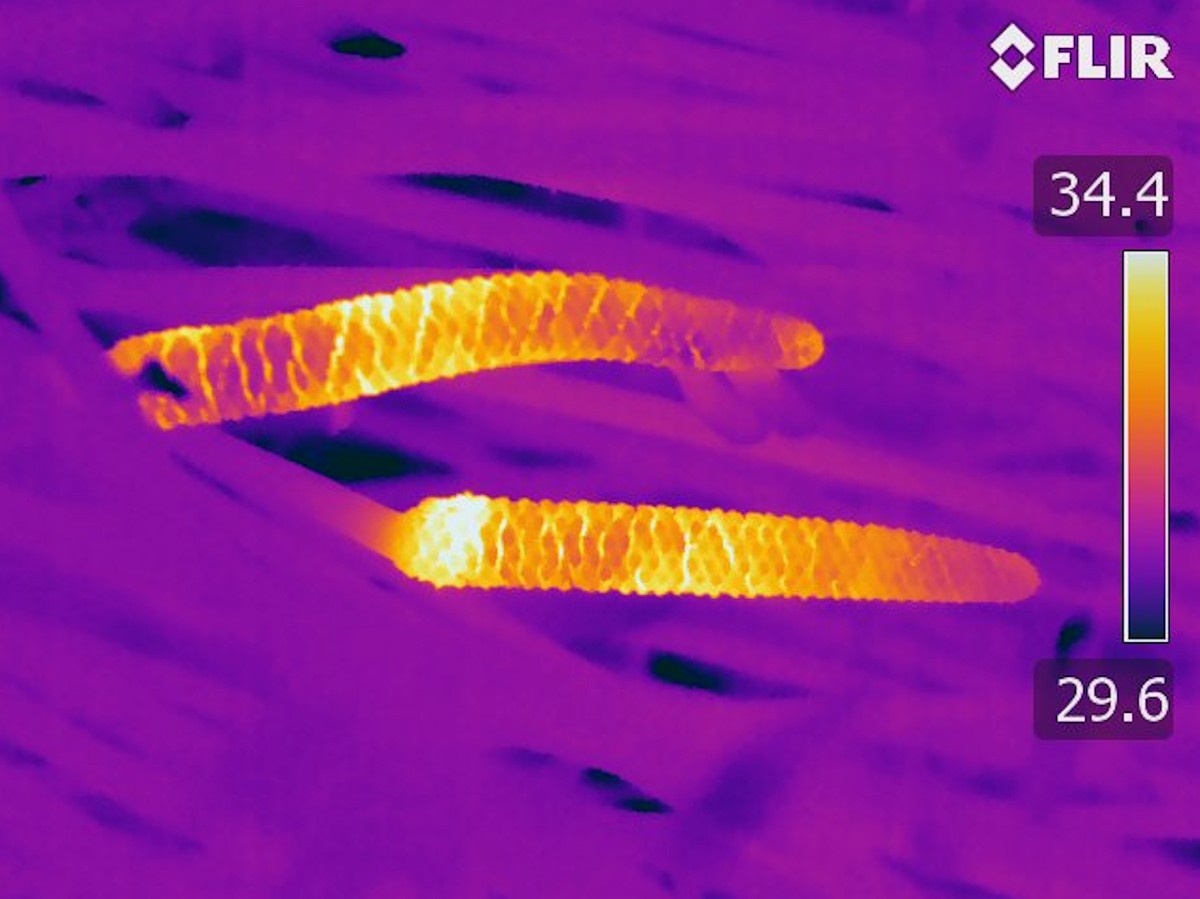

Cycads are thermogenic, meaning they actively produce heat, with some species reaching temperatures up to 15°C (27°F) warmer than their surroundings. Researchers confirmed that beetles are drawn to the warmest parts of cycad cones, even when other cues like scent are controlled. Experiments using ultraviolet dye showed beetles consistently visited warmer regions, indicating heat is a direct attractant.

When researchers heated 3D-printed cones and covered them with plastic to prevent thermal conduction through touch, beetles still preferred the warm cones over unheated ones, proving infrared radiation itself is the signal. The beetles’ antennae contain TRPA1, a heat-sensitive ion channel also found in snakes and mosquitoes, tuned to the specific temperature range of their host plants. This suggests beetles are biologically equipped to detect and respond to cycad heat.

The Evolutionary Puzzle of Flowering Plants

This research sheds light on a long-standing evolutionary question: why did flowering plants (angiosperms) diversify so rapidly while cycads remained comparatively limited in species number? The authors suggest that infrared-based pollination may have restricted cycads’ ability to form specialized relationships with a wider range of insects.

Flowers can evolve complex color patterns, saturation levels, and hues, enabling them to target numerous pollinators. Cycads, however, can only adjust heat intensity, potentially limiting their diversification. Other plant biologists suggest that scent could also have helped cycads diversify, but flowering plants have the advantage of combining both scent and color for broader appeal.

“Multiple opportunities for diversification is probably better than one,” says University of Cambridge plant biologist Beverley Glover.

The findings represent a significant step forward in understanding plant evolution and the origins of pollination, suggesting that heat was a critical ecological interaction long before the age of flowers.