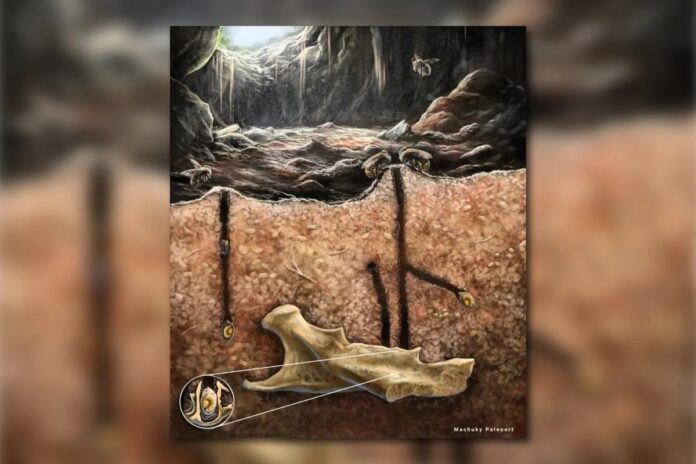

Thousands of years ago, in what is now the Dominican Republic, ancient bees exploited an unusual nesting site: the bones of extinct mammals. Researchers have found evidence of bees burrowing into the tooth sockets of fossilized rodents and sloths, a behavior never before documented in paleontology. This discovery offers new insight into the adaptability of bees and the complex interactions within ancient ecosystems.

The Gruesome Habitat

The findings originate from Cueva de Mono, a cave littered with the remains of extinct animals. Scientists initially explored the site for fossilized lizards, but soon realized they had stumbled upon a prehistoric “killing field” – the accumulation of bones regurgitated by ancient owls. Among these bones, they uncovered tens of thousands of jawbones containing smooth, cuplike structures within the teeth. These were not natural formations, but rather the waterproofed brood cells of solitary bees.

A Unique Nesting Strategy

The bees, species yet to be identified, seemingly took advantage of the pre-made cavities in the bones. The fossil record suggests this behavior occurred during the late Quaternary period (starting 125,000 years ago) with some of the bee activity dating back over 4,500 years.

Why bones? Researchers theorize that shallow or thin soils in surrounding forests drove bees to seek alternative nesting sites. The bones may have also offered an additional layer of protection against predators like parasitic wasps, acting as a natural “thermos” to safeguard developing larvae.

Communal Nesting in Ancient Bones

The evidence suggests repeated use of the bones over extended periods. Multiple nests were found within single tooth cavities, indicating communal nesting behavior. Bees may have been returning to the same bone structures generation after generation. This is supported by the discovery of nests in multiple soil layers within the cave.

This discovery highlights how even extinct animals can continue to play a role in ecosystems long after their death, serving as unexpected refuges for other species. The bee-bone relationship offers a unique perspective on prehistoric ecological dynamics.

The finding demonstrates that even in death, ancient organisms can sustain life. The bees weren’t just exploiting a resource; they were adapting to a unique opportunity left behind by predators.