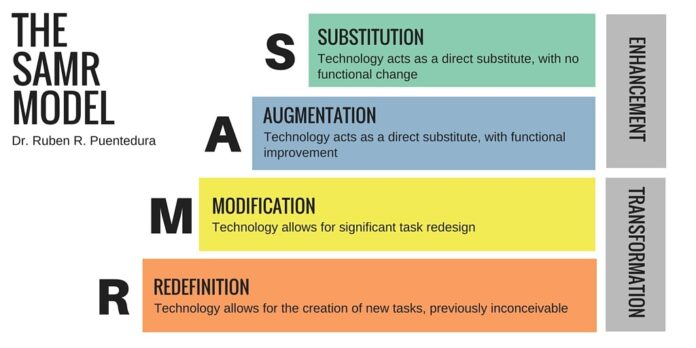

The SAMR model – Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition – has long been a cornerstone of discussions about technology in education. Introduced in the early 2000s, it offered a simple way to categorize how tech impacts learning. However, the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) reveals a critical flaw: SAMR treats change as inherently better when it isn’t. AI can amplify both positive and negative outcomes at any level of integration. The model needs a second dimension to account for whether tech strengthens or weakens teaching and learning.

The Original Model’s Limitations

Originally intended as a descriptive tool, SAMR quickly became prescriptive. Educators began to view Substitution as “basic” and Redefinition as the ideal, turning it into a staircase rather than a spectrum. In an AI-driven world, this linear thinking breaks down: AI can make simple tasks incredibly powerful, and advanced tasks deceptively empty. The single-axis approach of SAMR is no longer sufficient.

The Portrait of a Teacher Project and a Crucial Question

Recent research from the Ed3-led “Portrait of a Teacher in the Age of AI” initiative revealed this problem firsthand. Educators using AI across the SAMR spectrum consistently reported both positive and negative effects at every level. The question became clear: does SAMR need a second axis to assess whether changes are constructive or destructive?

Introducing the Positive-Negative Dimension

The key insight is that SAMR doesn’t just describe what kind of change technology introduces, but whether that change improves or degrades learning. Every level can be either beneficial or harmful.

- Substitution: Replacing paper quizzes with digital ones can free up teacher time for meaningful interactions, or it can automate grading without human review.

- Redefinition: AI can enable multilingual storytelling and creative expression, but it can also allow students to produce polished work without genuine effort or understanding.

This duality requires a reframing: SAMR is no longer a climb from “less innovative” to “more innovative.” It’s a two-axis system:

- Mode of Integration: (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition)

- Direction of Impact: (Negative ↔ Positive)

Four Key Nuances of the New Model

This expanded view reveals critical insights:

- Level Doesn’t Predict Quality: Substitution can be as effective as Redefinition if implemented thoughtfully.

- Efficiency Can Mask Erosion: Time saved through automation can either enhance teacher-student connections or replace them entirely.

- Redefinition Can Be Hollow: AI can create superficial learning gains without genuine depth.

- The Deciding Factor is Relational: Positive uses strengthen relationships, feedback, and access; negative ones weaken them.

Beyond Sequential Thinking

Another misconception is that SAMR is a sequential progression. Teachers don’t necessarily move from Substitution to Redefinition. AI makes this even less predictable; a teacher might start with Redefinition using simulations, then revert to Substitution for material generation to free up time for one-on-one student support. SAMR is better understood as a set of modes useful under different conditions.

Reframing the Questions

The new model shifts the focus from perceived innovation to tangible impact:

- Does this AI use deepen human connection or weaken it?

- Does it expand teacher capacity or restrict it?

- Does it open opportunities for students or narrow them?

These questions prioritize the direction of impact, not the level of sophistication. Every level of SAMR can be excellent or harmful, depending on the practice.

Connecting to the Adoption Curve

Finally, SAMR interacts with the technology adoption cycle. Early adopters gravitate toward Redefinition, while later adopters start with Substitution for safety and ease. This reframing suggests that teachers aren’t stuck in certain levels due to lack of creativity, but because they are at different stages of adoption. Understanding this dynamic helps leaders set realistic expectations and provide appropriate support.

In conclusion, a two-axis SAMR model acknowledges the complexity of teacher practice, respects diverse contexts, and centers human judgment as the defining variable. As AI becomes more pervasive, the relevant question isn’t “How high on SAMR is this?” but: “Is this use of AI accelerating or slowing down learning outcomes?”