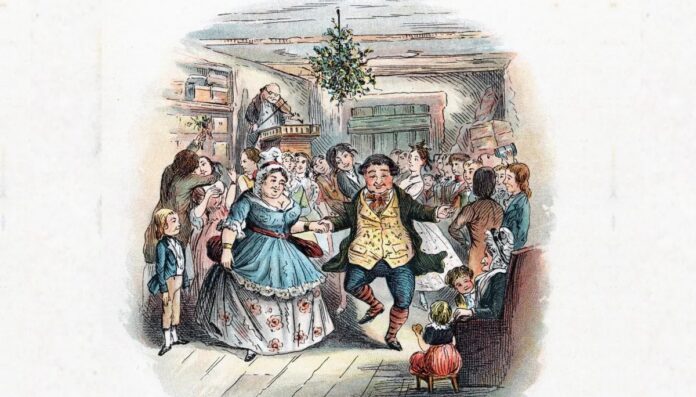

Mistletoe, the evergreen sprig synonymous with holiday kisses, has a history far more complex than its seasonal role suggests. While Bing Crosby’s classic “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” evokes images of snowy landscapes and mistletoe-draped doorways, the plant’s origins lie in ancient myths, medicinal practices, and a surprisingly brutal ecological reality.

A Plant Rooted in Myth and Medicine

For millennia, mistletoe wasn’t just decoration; it was revered. Ancient Greeks and Romans viewed it as a sacred plant, capable of bestowing fertility, warding off poisons, and even providing safe passage to the afterlife. Celtic rituals centered around oak and mistletoe, with high priests harvesting it with golden sickles for potent elixirs. Norse mythology tells of Baldr’s death by a mistletoe spear, a tale that some interpret as a symbolic representation of grief and eventual reconciliation – explaining why kissing beneath it became tradition.

Early physicians and scientists also saw mistletoe as a cure-all, treating conditions from epilepsy to infertility. Its perceived supernatural power likely stemmed from its ability to thrive even in winter, seeming to defy the natural cycle of life and death. By the 19th and early 20th centuries, newspapers tracked its seasonal availability, reflecting its widespread popularity.

The Parasitic Truth: “Dung on a Twig”

Despite its romantic associations, mistletoe is fundamentally a parasite. As plant biologist Jim Westwood notes, even those unfamiliar with its biology instinctively recognize it. It steals water and nutrients from host trees, though unlike some parasites, it can still photosynthesize. The plant’s nickname, translating to “dung on a twig,” reveals how it spreads: birds eat its sticky berries, dispersing the seeds through their droppings. These seeds adhere to branches, ensuring germination and a new parasitic life cycle.

Mistletoe also contains toxins, potentially causing gastrointestinal issues and dermatitis in humans, with European varieties being more potent due to the presence of a ricin-like substance. Yet, its widespread appeal persisted, prompting both attempts at control and commercial exploitation.

A Modern Ecological Reality

Today, over 4,000 plant species live as parasites, and mistletoe remains ecologically significant. Its presence is easily observed – even from a car, as plant pathologist Carolee Bull points out – making it a “charismatic plant pathogen.” It thrives across the U.S. in over 35 states, particularly in the Southeast, Southwest, and Pacific Northwest.

The plant’s history underscores a simple truth: it’s a successful strategy to steal resources rather than produce them. So, next time you stand beneath the mistletoe, remember it’s not just a symbol of romance but a resilient, ancient parasite with deep roots in both myth and biology.