This article revisits scientific discoveries and observations from three distinct eras—1876, 1926, and 1976—to illustrate how our understanding of the world has evolved. Each period reveals unique insights into natural phenomena, human adaptation, and even the frustrating realities of bureaucracy.

The Late 19th Century: Postal Chaos and Sonic Dunes (1876)

In 1876, a new postal law passed by the U.S. Congress was met with immediate criticism for its impracticality. The law doubled postage rates on newspapers, magazines, and goods, implementing a tiered pricing system based on distance. The problem wasn’t the cost increase itself, but the sheer complexity: citizens were expected to know precise distances between post offices, a logistical nightmare for a population without widespread mapping or standardized measurements. This reveals a recurring tension: well-intentioned policy often fails when it ignores the practical limits of implementation.

That same year, scientists began to document an unusual phenomenon: booming dunes. These sand formations in regions like Nevada were found to emit low-frequency sounds—resembling cello notes—when disturbed. Researchers discovered that digging trenches or sliding sand downhill triggered the vibrations, which could even be felt as a mild electric shock. This discovery underscores a fundamental aspect of scientific inquiry: nature holds surprises in unexpected places, and even seemingly inert environments can produce remarkable phenomena.

The Interwar Years: Norse Decline and Avian Misnomers (1926)

By 1926, archaeological excavations in Greenland revealed the fate of early Norse settlers. Dr. Poul Nørlund’s work at Herjolfsnes unearthed well-preserved relics, including skeletons, garments, and tools. The findings indicated that a sudden climate shift—growing ice blockage—led to the colony’s decline. The Norse colonists, though in contact with Europe until recently, were physically weakened by the worsening conditions and were outmatched by the indigenous Eskimos. This is a stark example of how environmental pressures can reshape civilizations and highlight the importance of adaptation.

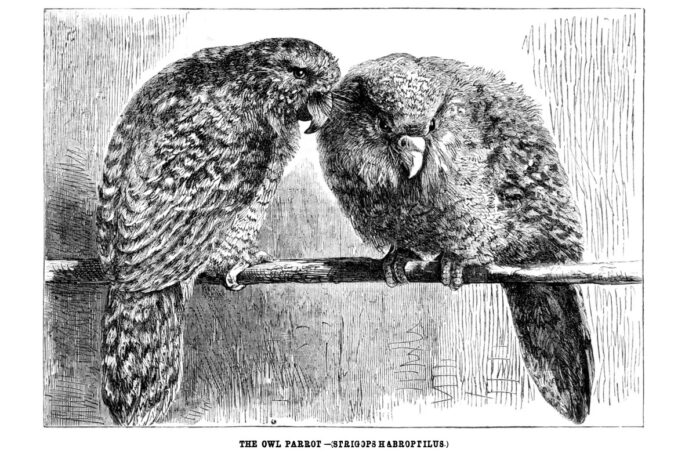

Meanwhile, ornithologists poked fun at the arbitrary naming conventions of American birds. The “Carolina Wren,” for example, was named despite being found across a far wider range. This illustrates a common human tendency to impose artificial order on nature through naming, even when the reality doesn’t fit the labels. The writer championed the wren for its musicality, industriousness, and optimism—qualities that transcend geography.

The Mid-1970s: Catastrophes and Biological Chaos (1976)

In 1976, mathematicians and biologists explored “Catastrophe Theory.” Pioneered by René Thom, the theory proposed that abrupt changes in systems—whether biological, social, or physical—could be modeled mathematically. The idea was radical: life itself is a series of disruptions, with cells and organisms constantly undergoing catastrophic transitions. The theory found applications in embryology, evolution, and even speech generation, suggesting that sudden shifts are not anomalies but fundamental processes.

The same year, scientists began studying the acoustic properties of dunes more systematically. By digging trenches in a Nevada dune called Sand Mountain, they confirmed that the booming sounds were loudest when the sand was disturbed rapidly. This research underscored a simple point: even well-documented phenomena like squeaking dunes demand precise analysis to understand their underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, these snapshots from 1876, 1926, and 1976 demonstrate the enduring human drive to understand the world around us. From bureaucratic blunders to environmental collapses, from the mysteries of ancient settlements to the chaotic beauty of natural phenomena, science has consistently sought to make sense of a universe that often defies easy categorization.